Out today is the fourth peer-reviewed article deriving from the search for Richard III’s grave. It focuses on the king’s bones and teeth, specifically what a few of them might tell us about where he lived at different times in his life, and how his diet changed. And once again, the scientific release occurs on the day Channel 4 broadcasts a new film about the dig.

The headline conclusions are:

- Richard III’s diet was impressively aristocratic – high in meat and fish (some of which were from the sea) – though for a period from the age of around five it was heavier on grains; this youthful gruel episode was offset by greater luxuries when he was king, including more freshwater fish and wildfowl, and wine

- The study supports Richard’s known origins in Northamptonshire, but suggests he had moved out of eastern England by age seven, and lived further west, possibly in the Welsh Marches (the borderland area between Wales and England), returning to eastern England as an adolescent or young adult.

There will be sceptics. There will be historians thinking, “Fancy that, Richard III lived in eastern England and had a posh diet, who would’ve guessed?” Google found me a press article on Friday (that its publisher probably believed not to have been online ahead of the Sunday embargo) that opened, “Research conducted on the composition of Richard III of England’s teeth and bones confirm what we already knew”. Such writers miss the point.

First, this is real, new evidence, not stuff that is just assumed. Secondly, and importantly, the science here is quite complex, and though well established, still growing – there is all to prove (or disprove) in an area that offers much in understanding ancient lives. The very rare chance to study an identified historical individual, with a good record, allows the science to be tested against prior information.

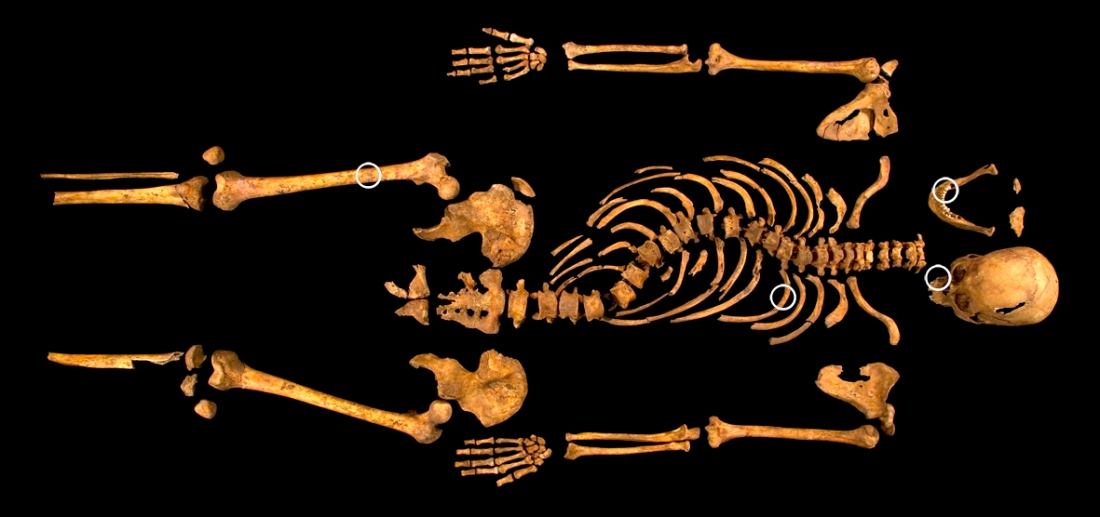

By 1995, scientists had been analysing chemical isotopes (comparing the proportions of particular “forms” of different elements) in ancient human bone and teeth for some years. The idea was to identify aspects of diet (high in seafood, for example) or migration (eg a skeleton with radically different values from others in a cemetery might suggest an immigrant). But in that year a key paper took the research into a new area. A South African team proposed that by analysing different parts of a single skeleton, changes in diet and residency patterns might be observed occurring within a person’s lifetime. The principle was that different bones and teeth grow at varied rates or times, creating chemical signatures that relate to events in the individual’s life during those different growth episodes.

We saw this idea being exploited in the BBC TV series, Meet the Ancestors, when teeth analyses regularly indicated a surprising amount of movement around (or even beyond) the UK among people who had previously been assumed to have been pretty static. Judith Sealy and colleagues concluded their 1995 paper by saying, “It is sincerely to [be] hoped that, in the future, work such as this will have access to named individuals whose historically attested dietary histories may be checked against the chemical findings.” As Angela Lamb and Jane Evans (of the British Geological Survey) point out in the new study, examinations of known people remain scarce (off the top of my head, I can’t think of another one).

Even with anonymous people, such comprehensive studies with human remains are still quite rare. The authors of the new paper think only two large scale projects of this kind have been conducted in the UK. One concerned an extraordinary find in Dorset, where the bodies of around 50 decapitated men had been slung into a mass grave – stable isotope research by a team that included Jane Evans established they were Vikings, probably slaughtered by local Anglo-Saxons (the dig featured in British Archaeology May/Jun 2014/136).

What makes the new study particularly interesting is that while we can guess the king ate well, we knew little in detail about his diet (even if we have menus, can we be sure what the man actually ate?). And while we knew where he was born, and where he spent most of his life, there was apparently little information about his residency in childhood and early adult years. So we have a mixture of known and unknowns, with stuff to learn and test. The science is tricky (and the paper unfortunately poorly written and edited – try the very first sentence: “The discovery of the mortal remains of King Richard III provide an opportunity to learn more about his lifestyle, including his origins and movements and his dietary history; particularly focussing on the changes that Kingship brought.”). But keep an eye out, this will create much specialist interest, and further related studies and commentaries are likely.

References

“Multi-isotope analysis demonstrates significant lifestyle changes in King Richard III”, by Angela Lamb, Jane Evans, Richard Buckley & Jo Appleby, Journal of Archaeological Science (August 2014)

“Beyond lifetime averages: tracing life histories through isotopic analysis of different calcified tissues from archaeological human skeletons”, by Judith Sealy, Richard Armstrong & Carmel Schrire, Antiquity (1995)

The previously published peer-reviewed articles from this project are:

“‘The king in the car park’: new light on the death & burial of Richard III in the Grey Friars church, Leicester, in 1485”, Antiquity (May 2013)

“The intestinal parasites of King Richard III”, The Lancet (September 2013)

“The scoliosis of Richard III, last Plantagenet King of England: diagnosis and clinical significance”, The Lancet (May 2014)

Sealy et al. aren’t “An Australian team” – they are/were from Cape Town, South Africa

Many thanks for noting my mistake (I’ve corrected the blog above). For the record, the originally South African writers are all at the universities they were when the Antiquity paper was published: Judith Sealy is now head of the Department of Archaeology at the University of Cape Town; Richard Armstrong is at the College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences, the Australian National University Canberra; and Carmel Schrire is distinguished professor of anthropology at Rutgers University, NJ.

Speaking of lazy errors, it’s interesting to see how the press are covering this story. It’s mainly about the booze – note the progression in these headlines from a pint a day to over five, followed by the inevitable death, the sure scientific proof of alcoholism. “My kingdom for a pint: Richard III loved his drink” (Sunday Times); “King Richard III downed a bottle of wine every day to cope with pressure” (Mirror); “Revealed: how becoming king turned Richard III into a drunk” (Herald Scotland, which continues, “King Richard III was driven to drink by the pressures of power, according to new evidence”); “Richard III drank 3 litres of booze a day, no wonder he was found dead in a car park” (Metro).

The Journal of Archaeological Science article, and Elsevier’s press release, do highlight “a diet filled with expensive, high status food and drink”. A typical quote from Angela Lamb (in the Independent) notes that in the last three years of the king’s life, his alcohol intake “was a considerable step up from what was his average drinking before”. But only in the press is this equated with a love of drink, stress or even illness. The scientific study links the alcohol (suggested to be wine) to the privileges of the king’s high wealth and status – in modern terms, a very different story.

The Independent’s headline takes a different tack: food. “Swan, egret, heron: the Richard III diet revealed”. Now while the science is suggested to indicate “an increase in consumption of freshwater fish and birds”, the varieties come from historical documents of the time, not specifically linked to the king.

Hi Mike, Nice summary.

Hi Jane, Nice work.

Reblogged this on hiddenhistoryhub and commented:

Useful perspective