1. It’s beautiful

The best analysis of the statue is by TGH James. An Egyptologist at the British Museum, he described it in full, for the first time, in 1963, after someone had tipped him off about it (“The Northampton statue of Sekhemka”, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 49, 5–12).

According to James, the man is identified by an inscription on the base beside his left foot (“Inspector of scribes of the house of the master of largess, one revered before the great god, Sekhemka”). By his right foot sits Sitmeret (“She who is concerned with the affairs of the king, one revered before the great god, Sitmeret”). She is carved, it seems, as a real woman, her left arm wrapped affectionately behind Sekhemka’s right leg, the hand protruding below his knee – the other half, as it were, of his identity. No relationship is described, but James felt “the intimate posture” means she is probably his wife.

While Sitmeret’s beauty is displayed in full sculptural glory, Seshemnefer (“The scribe of the house of the master of largess, Seshemnefer”), is represented as a more stylised two dimensional frieze, standing beside Sekhemka’s left leg. The facts of his position and that he is named, unlike the other men around the seat, suggested to James that Seshemnefer may be Sekhemka’s son.

On the open papyrus scroll which Sekhemka holds on his knees, says James, is a list of 22 offerings, “those normally found at the beginning of the standard offering-lists of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties”. They include such things as “festival perfume, one jar” and “Breakfast: bread and beer”.

Around the sides of the square seat are five men in the same style as Seshemnefer. Three on the back carry jars of ritual liquids, an incense censer and strips of cloth. On the left side (as seen from the front) one carries a goose and two, long-stemmed papyrus flowers; the other a calf. On the right two men each old a goose.

Viewing the statue for the first time on the landing at Christie’s, where it was superbly lit and surrounded by an eclectic group of masterworks in an atmosphere of reverence and superior quality, I was struck by the sculpture’s presence. The soft, warm limestone, the extensive paint, the composition, the manner of carving and the style – a fine execution of Old Kingdom conventions around 2400–2300BC – make this a stunningly beautiful and moving object. James concurs, if holding back a little: “It may be the case that the Northampton statue of Sekhemka cannot be included in the small group of master sculptures which especially distinguish Old Kingdom art; it remains, nevertheless, a piece of fine quality.”

2. The Brooklyn Museum has one too

The statue was recorded for James by the Northampton photographers H Cooper & Son. Somehow, James says, some of the prints erroneously arrived on the desk of Bernard Bothmer, another prominent Egyptologist, at the Brooklyn Museum. This chance, if so it was, allowed James to describe a statue of Sekhemka at the Brooklyn – we’ve got one too, said Bothmer! James agrees that it is the same Sekhemka , though this “is not susceptible of absolute proof” – the top half of the man is missing, and overall the sculpture, made in harder “diorite”, is less elaborate. James goes on to discuss the possibly of matching either sculpture to one of the tombs known at Giza and Saqqara also attributed to a Sekhemka, in particular mastaba C19 at Saqqara. But he rejects the idea, on the grounds that C19 was found late in 1850, while the Marquess of Northampton was there in the same year, but earlier (and see below on the statue’s history). But he does accept the attributed provenance of both statues to Saqqara.

3. The statue seems to have been well looked after

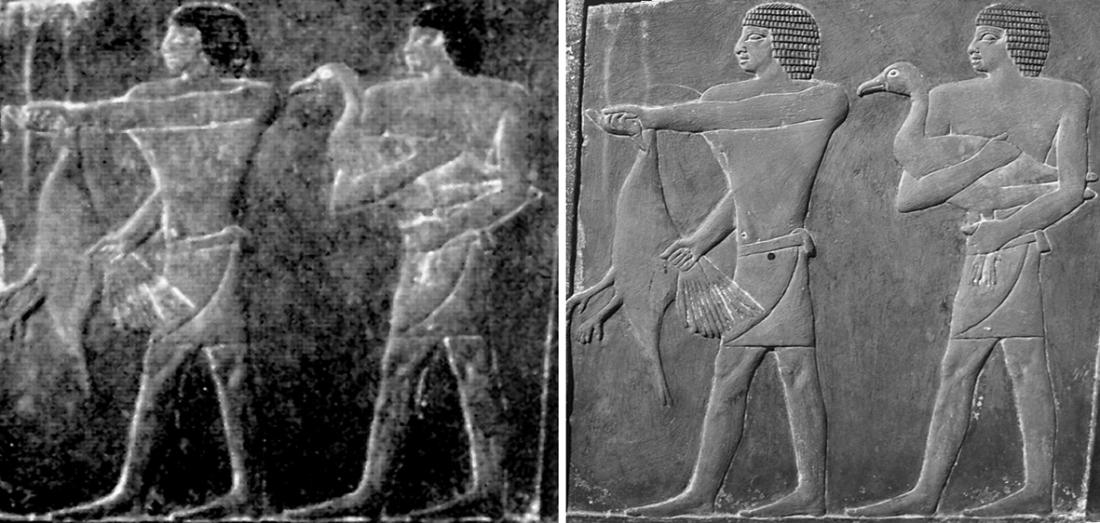

On the limited evidence of James’ photos published in 1963 and my own taken this week, there seems to have been little if any damage to the stone or the fragile paintwork, at least over the last 50 years. In a couple of points there are differences that seem to have something to do with the paint, though it’s difficult to know what these mean. In the photos below, I’ve reduced mine to monochrome (to the right in both cases) to make comparison easier. In the first pair, there is a dark line between the legs that appears not to have been there in 1963. And in the second, a small blob below the belt of the left figure.

4. Northampton Borough Council did not have a clear right to sell the statue

But they believe they had bought that right – for a combination of £40,000 of legal advice, and £6.3m given to Lord Northampton. An expensive purchase.

In 1880 the fourth Marquess of Northampton and the Borough of Northampton signed a Deed of Gift. The Museums Association has put the entire, short document online, from which I’ve extracted some key passages (see above).

The gift was huge, mostly of fossils in cabinets (“a great number of specimens”): it is titled “Deed of Gift of Geological Collection”. There was also, it says inside, “a collection of Egyptian Antiquities including four framed specimens of Wall painting and papyrus and other objects”. The statue is not mentioned.

In 1963 TGH James wrote that the Northampton Museums and Art Gallery records “contain no precise information concerning [the statue’s] acquisition, but it is known that it was presented in about I870 by the third Marquis of Northampton.” He notes a press cutting, dated 1899, describing the contents of the Abington Museum (which until shortly before James wrote his article, had displayed the statue “in relative obscurity”). This says that “in the Egyptian Room are specimens of papyri… a case of small Egyptian articles collected by Spencer Joshua Alwyne Compton, President of the Royal Society, and other Egyptian figures”. Compton was the second Marquess of Northampton and a founder member and president of the Royal Archaeological Institute. He travelled to Egypt in I850. “It was on this journey in all probability”, says James, “that he collected the Egyptian antiquities which eventually found their way to the Abington Museum.” “There seems to be no good reason”, he concludes, “for doubting that the statue of Sekhemka, presented by the third marquis, was acquired by his father on the same journey.” The fourth marquess then gifted the statue, already in the borough’s collection, in 1880.

There may be “no good reason” for doubting that the statue was acquired by the second marquess in Egypt. But is there good reason to believe it was?

The second marquess was in Egypt in 1850. The third marquess is said to have presented the statue to the Borough of Northampton around 20 years later. A decade after this the fourth marquess gifted a collection of geological specimens and Egyptian antiquities to the borough. A further two decades on, a newspaper reports that the borough was exhibiting “specimens of papyri… a case of small Egyptian articles collected by Spencer Joshua Alwyne Compton [the second marquess] … and other Egyptian figures”.

Christie’s translate that as follows:

“Acquired by Spencer Joshua Alwyne Compton, 2nd Marquess of Northampton (1790-1851), in Egypt between December 1849 and April 1850. Presented to the Northampton Museums and Art Gallery by either Charles Douglas-Compton, 3rd Marquess of Northampton (1816-1877) or Admiral William Compton, 4th Marquess of Northampton (1818-1897).”

However, none of this is provable, at least on the evidence we have. Nowhere is the statue specifically mentioned in the early records, including the 1880 deed of gift: all we have is James’s assertion, made in 1963, that the statue was then “known” to have been presented by the third marquess, in about I870. The press cutting is of dubious relevance. We all know how easy it could be for a press journalist or subeditor to confuse one marquess with another. In fact, taken literally, the piece seems to imply that the statue was NOT part of a Northampton bequest. It refers to “a case of small Egyptian articles collected by [the second marquess] … and other Egyptian figures”. The statue is arguably unlikely to have been inside “a case of small Egyptian articles”, and if not, was among “other Egyptian figures”, whose source is unstated.

On the face of it, the council has no documentation to prove its ownership of the statue.

By 2013, however, it’s clear that both the council and the current Marquess of Northampton believed it did own it. For in January last year, the marquess threatened the council with legal action if it sold the statue – on the grounds that the deed of gift says it can’t sell anything without the collection reverting to the fourth marquess’s family. The council was then understood to be saying that as the statue wasn’t mentioned in the deed, it wasn’t included in the gift.

So, the council’s right to sell the statue depends on it being able to show that it owns it as a result of a gift in 1880. But to get around the fact that the deed actually says they can’t sell it, they argue the deed did not include the statue. But in that case… no, this is getting too confusing for me.

What seems clear, however, is that the council got the marquess’s approval by offering him a load of dosh – 45% of the sale proceeds. That turned out to be a good deal for the marquess, who surely was not expecting to get £6,300,000 out of the deal (or “around £6million” in the words of a council for whom mere thousands are presumably too trifling to worry with)

Certainly, it worked out better than the marquess’s attempts so far to make money from the Sevso treasure. As British Archaeology reported in 2007, this fabulous hoard of late antique silverware, valued at £100m, was caught up in an unfortunate history of illegal excavations and export (from Hungary). Lord Renfrew wrote recently, setting the hoard into context, of a “tangled tale of greed and irresponsibility by ‘collectors’ in high places who might have known better, seeking a quick and easy profit and showing little respect for the world’s archaeological heritage”. The Marquess of Northampton bought the hoard in 1987, hoping to sell it to his advantage: but his plans ran into trouble when the hoard’s history became public. This is the same man of whom the council’s chief executive has said, “We know Lord Northampton and his son Lord Compton very well, they are true supporters of ours and they have already given to our work around alleviating food poverty”.

In fact the marquess was so pleased with the sale of the Egyptian statue, he gave £1m back to the council! Thus everyone wins. The marquess trousers £5.3m for something that he could never have touched, had not the council, as it saw it, broken the terms of a deed of gift made by an ancestor of his. And the council gets £1m from the sale it can spend on whatever it likes: this didn’t come from their part in selling the statue, so it’s not “ring-fenced for the Museum Service” and can instead be spent on “essential funding for some of our smaller voluntary and charitable groups providing excellent community cultural activity across our county”. These might include, said council chief executive Victoria Miles, “a world war memorial group, a community choir, volunteer networks supporting a heritage site or local museum, young people engaging with arts and music activities or any number of good causes in the arts and heritage field”. So you can sell your statue promising to spend all the proceeds on a new museum extension, and still get a million quid for a community choir.

I’m not sure if the council’s thinking on this statue over the years has been entirely consistent.

5. The Museums Association did not approve of the sale

Initially, the council told the Museums Association’s Ethics Committee in 2012, it wished to sell the statue, then valued at £2m, to raise funds for “the restoration of Delapre Abbey, improvements to the museum service and/or other cultural or heritage projects”. The committee said that plans for spending the money were too vague for it to advise fully on the proposed sale.

Later in 2012 the committee told the council off over a public consultation about the sale. The council had asked people if the £2m sale proceeds should be spent on the restoration of Delapre Abbey, the expansion of Northampton Museum and Art Gallery, the establishment of a National Shoe Museum or the development of Abington Park Museum. It didn’t ask if it should sell the statue in the first place. And neither did it tell people about something they were unable to see (the statue not being exhibited). I have strong doubts that had the people of Northampton been able to see what I saw in Christie’s last Friday, they would have wanted their statue sold.

In January this year, by when the statue’s estimated value had risen to £4m–6m, the Museums Association “urged Northampton Borough Council to rethink its sale”. Unless the council sought “alternative sources of capital funding”, said David Fleming, chair of the ethics committee, “the MA cannot endorse the sale.” There is no sign that the council undertook such a search. Thus the sale was not “endorsed” (recognised/validated/approved, take your pick) by the Museums Association.

6. The Art Fund did not approve of the sale

In a statement issued the day after the sale, the Art Fund said:

“We remain strongly opposed to deaccessioning any item for financial reasons except in exceptional circumstances, where the funds will directly benefit the museum collection and only after all other options have been explored. This is not the case with the sale of Sekhemka and as such, having gone against the sector’s ethical guidance, it risks being stripped of its accredited status.”

[Added July 15] And Arts Council England is no more impressed. “Those who choose to approach the sale of collections”, said Scott Furlong, director of ACE’s acquisitions exports loans collections unit, “cynically or with little regard for the sectoral standards or their long-term responsibilities, will only further alienate both key funders and the public who put their trust in them to care for our shared inheritance.”

With the Museums Association, the Art Fund and ACE unhappy about the sale, Northampton’s chances of raising money through conventional funding streams may now be lower than they were. In the long run, the sale could cost them more in lost grants than it made in the auction room. The impression one gets is that the council was more impressed with the promise of a big sale cheque, than they were inspired by the idea of putting in the work to come up with well thought out imaginative projects that would attract suitable sponsors. If only… they would have had the most beautiful Egyptian statue to show off, that somehow – I’m guessing the story will be out there, it’s just waiting for an obsessive researcher – is at the heart of the borough’s 19th century history.

7. Christie’s did a good job

One might be tempted to cast Christie’s as a villain in this story, but really they were doing what was right for their client, in a legal sale. They displayed the statue proudly in London for public view (I imagine better than it had ever been displayed before), described it in a well illustrated catalogue on public sale (and free online), and achieved a remarkable price. They handled a protest during the sale with quiet dignity. It would not have been in their client’s interest to have noted the continuing debate about the ethics of the sale, and they duly did not.

They got well paid for all this. The statue sold for £14m. “Buyers commission” took that up to £15,762,500 – the buyer paid Christie’s an additional £1,762,500. On their standard prices, Northampton council will have paid Christie’s at least £4,700 for the catalogue entry (photos on the front cover and six full pages, plus eight further images at the smallest charge size). More significantly, they will be paying Christie’s an undisclosed seller’s commission. By any standards, those fees add up to a good profit – and the sale will have brought the auction house good PR where it counts.

When Northampton Borough Council said in a statement after the sale that it “will retain around £8million” after paying off the marquess, it hadn’t apparently worked out its sums in the rush. Firstly, 55% of £14m (the council’s agreed share) is £7.7m, not £8m. Then it has to pay Christie’s for the catalogue, its commission (typically 10%) and any other agreed costs such as marketing or transport. Let’s say that gets us to about £6,925,000. For most of Northampton’s tax payers I’d wager that’s a big difference from £8m. Of course, I’d be very pleased to correct and revise these estimates if someone would like to help me out with real figures.

This story has only just begun. We don’t yet know who bought the statue (Christie’s has promised to tell us in due course). The Museums Association has to make up its mind whether or not it would have advised the marquess not to sell, had the statue not already been sold. The effect of the sale on prospective grant givers has yet to be seen, as has its effect on the antiquities market as a whole (though I’d say the argument by ICOM that the sale of the statue “may result in an increase of illicit excavation and trafficking of antiquities in Egypt” is an odd one; the statue might still have been in the ownership of the marquess’s family, and have gone out as a private sale which the law, and most observers, would regard as legitimate – the issue is less that the statue has been sold per se, than that it was held in trust by a public body which should have been above such action). Importantly, we do not yet know what will happen to the statue: will it disappear from sight (and researchers, for whom there is apparently much still to learn), or be exhibited somewhere?

[Added July 15] And for those who like to take care of their money, whether it’s their own or held on behalf of others, it’s worth bearing in mind an important fact. Sekhemka has now been valued at £14m. It used to belong to the people of Northampton. It no longer does, and in return they received probably less than £7m. Does that sound like good housekeeping to you?

[Added January 2022] This originally went out under the headline, “Six things about Sekhemka”. Then i realised there were two 5s…

As always, unless otherwise noted, all photos are mine.

“In the first pair, there is a dark line between the legs that appears not to have been there in 1963.”

I believe that’s just a shadow!

The statue looks like it was lit by a light from either side, so each leg is casting a shadow inwards. Those shadows aren’t dark because they’re also lit from the other light. Where the shadows overlap, and neither light is reaching, you get the dark line.

I believe you may be right!

excellent post as always!

Brilliant article. I researched Sekhemka for my museum diploma. I like you am no further to discovering his true history. You have covered the story brilliantly. You encapsulate all the facts all clearly as possible.

Did you see the statue in Northampton, or ask to see it? The council seem to think that lack of inquiries about the statue when it was off display for a few years means no one was interested in it – the town didn’t want it, so why no sell it?

au contriare…There were over 100 requests in the past few years…ALL were denied….The council were on their own agenda….

Scrimnet that’s interesting, can you show us evidence for that?

There’s a nice video by a BBC journalist (doesn’t he deserve a byline, BBC?) shot outside Christie’s just after the sale (look for me in the background talking to protestors…). There’s a clip in which he interviews David Mackintosh, leader of Northampton Borough Council, who says: “[The statue’s] not been on display in Northampton for over four years. Nobody’s really come to us and asked for it to be on display or to see it.” This is neither here nor there when it comes to assessing a collection’s worth or public interest, but it would be good to clear it up. Had people asked to see it, or had they not?

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-northamptonshire-28257714

There were hundreds of requests to see the statue in Northampton during autumn 2012 and spring 2013 by schools, WIs and other societies – all were told that statue would be on display before sale and they would be invited to view it; taking a school class to Christie’s is hardly child friendly ?

There have been objections to the sale since August 2012! Thank you to Mike for an excellent and balanced article on whole issue.

Gunilla, I’d like to think that Christie’s would welcome school parties with open arms – what an educational experience! But I recognise that’s not necessarily their job, more one for a museum service. Speaking of which, can you show us evidence of any of these requests to see the statue? It would move things on if we could see a written request to view Sekhemka, and the response from the council, especially if that included a promise to an invited viewing. The older the better, as I’m guessing that the council would say recent requests were inspired by protest rather than curiosity.

Excellent summation and analysis of a messy and lurid chapter on Cultural Patrimony. Am re-blogging; thanks for such a clear write-up.

Reblogged this on DIANABUJA'S BLOG: Africa, The Middle East, Agriculture, History and Culture and commented:

Excellent write-up about the history of the sale of Sekhemka –

Reblogged this on Adventures in History and Archaeology and commented:

Last week, this statue was sold to a private owner. Historians, archaeologists and scholars from all fields lament this sale as the statue is important not just to Northampton’s collection but to scholars worldwide.

A valuable summary of the this depressing episode. I cannot agree that Christies were quite so blameless, however. They surely have a duty to try and establish that the vendor does actually have the right to sell a piece! Perhaps the most depressing aspect is the way elected council officials ignored public requests and appeals, ignored professional advice, and used public money to fund a legal team to railroad through a very dubious deal. This is not what you expect in Britain. …and just why were they so very keen to force this sale through? To fund a choir group? To build a museum extension? P-lease!

I think Lord Northampton as a senior Freemason engineered the whole scheme and ordered the lower level Freemasons on the Council to organise a serious of events to make himself a pretty penny. The whole sorry story stinks to high heaven.

No one would believe the machinations and veil of secrecy which has surrounded this sale from beginning to end. No party involved in the sale has answered any questions as to its legality. I will never believe that the sale was legal unless I see some documentation to that effect. The ruling party of Northampton Borough Council led by Councillor David Mackintosh, a man who listens to no one and appears to run Northampton singlehandedly, should hang their heads in shame. Losing Sekhemka, our greatest cultural asset, which should have been celebrated to bring tourism into Northampton, and now losing Accreditation show Councillor Mackintosh, Prospective Parliamentary Candidate, is unfit to be a Council Leader or MP. This story is not over yet.

It shows how corrupt Northampton has become and how Freemasons have systematically plundered Northampton. Look at the Guildhall to see how they stamped their evil mark on Northampton.

Since the Sekhemka scandal David Mackintosh has been involved in more skullduggery involving a massive loan £10.5 million, to the local football club of which around £30,000 slipped into his hands. He used this to become an MP, after it became apparent what he had done he was deselected as Tory candidate in the last election. These Freemasons get away with murder!

To be clear on this, police investigations of alleged financial transactions involving David Mackintosh, Northampton Borough Council, Northampton Town Football Club and 1st Land Ltd, reported by the Guardian and the BBC in 2015 and 2016, do not appear yet to have been completed or published. We do not know what happened that might have been wrong, if anything. Under local pressure, Mackintosh decided not to stand at the last general election.