Three months ago Christie’s London sold an ancient Egyptian statue for £14m (estimate £4–6m). Today Bonhams London were to sell a group of ancient Egyptian antiquities (estimate £80–120,000). The lots had things in common. Both were taken out of Egypt (just) over a century ago, and both were in museums open to the public. Both had been given to those museums (the first in Northampton, the second in St Louis) on the understanding that they would remain in the public realm (in the case of the statue, that was stipulated in a legal document). And both were taken off display by the institutions in whose care they happened at the moment to be, and given to a London auction house with a view to making a profit, with no restrictions on where they should end up. Both sales were greeted with protest from some in the archaeological community.

There are differences, too. Northampton Borough Council has been almost boastful of its achievement, dismissing criticism. Yesterday the Museums Association barred Northampton Museums Service from membership for at least five years, not the first sanction. “We have already notified them that we have resigned from the Association and have no desire to ever re-join,” said a spokesperson for the council. “We could not see what benefit it offered to our museums.”

Perhaps to avoid a dispute over the original bequest, the council paid a very large sum of money to a descendent of the private donor. This option would seem not to have been available to the Archaeological Institute of America St Louis Society, which acquired the artefacts promoted by Bonhams from an excavation by the British School of Archaeology in Egypt (BSAE). On September 26, Alice Stevenson, UCL Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology, and Chris Naunton, of the London-based Egypt Exploration Society, issued a statement condemning the sale. They explained that “The regulations of the BSAE stipulate quite explicitly that any antiquities granted to it by the Egyptian authorities were to be distributed to ‘public museums’.”

On September 30, the parent body of the St Louis Society, the Archaeological Institute of America itself, expressed “the deepest concern” over the sale. That would have gone ahead today (at 12.39pm, as it happened). But as I was sitting at my screen preparing to watch the sale online, at some time between 10.05am and 10.38am, Bonhams revealed that they had withdrawn the lot. That’s good news for now, and we await to hear what happened. But meanwhile, what else went under the hammer?

This was a regular antiquities sale, the sort of thing Bonhams is getting pretty good at. I took screen grabs as the lots went by. Here are some, with the full provenance details from the catalogue. In all of these shots, the “current bid” was the highest (usually resulting in a purchase), the ranges (£6000–8000, etc) Bonhams’ pre-sale estimates.

Lot 79: American private collection, San Francisco, since the 1960s.

Lot 80: Robert Knight Collection, UK, purchased in 2006. Bonhams London, 27 April 2006, lot 131. London art market.

Lot 80: Robert Knight Collection, UK, purchased in 2006. Bonhams London, 27 April 2006, lot 131. London art market.

Lot 81: J.A. Person Collection, California, inherited in 1992. Deceased estate of Dr Charles R. Paul (d.1992), Los Angeles, California, formed between 1965-1985. Accompanied by a copy of a Survey Appraisal of the deceased estate of Charles R. Paul, dated 10 November 1992, no.18.

Lot 81: J.A. Person Collection, California, inherited in 1992. Deceased estate of Dr Charles R. Paul (d.1992), Los Angeles, California, formed between 1965-1985. Accompanied by a copy of a Survey Appraisal of the deceased estate of Charles R. Paul, dated 10 November 1992, no.18.

Lot 84: American private collection, acquired in the late 1980s in New York. (Curious how the head and hands are missing, though who knows, perhaps they will appear in another auction?)

Lot 84: American private collection, acquired in the late 1980s in New York. (Curious how the head and hands are missing, though who knows, perhaps they will appear in another auction?)

Lot 90: Japanese private collection, acquired from Alain de Montbrison, Paris in 1988.

Lot 90: Japanese private collection, acquired from Alain de Montbrison, Paris in 1988.

Lot 97: Austrian private collection, Vienna, acquired on the Munich art market in the 1990s.

Lot 97: Austrian private collection, Vienna, acquired on the Munich art market in the 1990s.

Lot 98: Austrian private collection, Vienna, acquired on the Munich art market in the 1990s.

Lot 98: Austrian private collection, Vienna, acquired on the Munich art market in the 1990s.

Lot 101: Christie’s, New York, 9 December 2008, lot 182. French private collection, Paris, acquired in 1985.

Lot 101: Christie’s, New York, 9 December 2008, lot 182. French private collection, Paris, acquired in 1985.

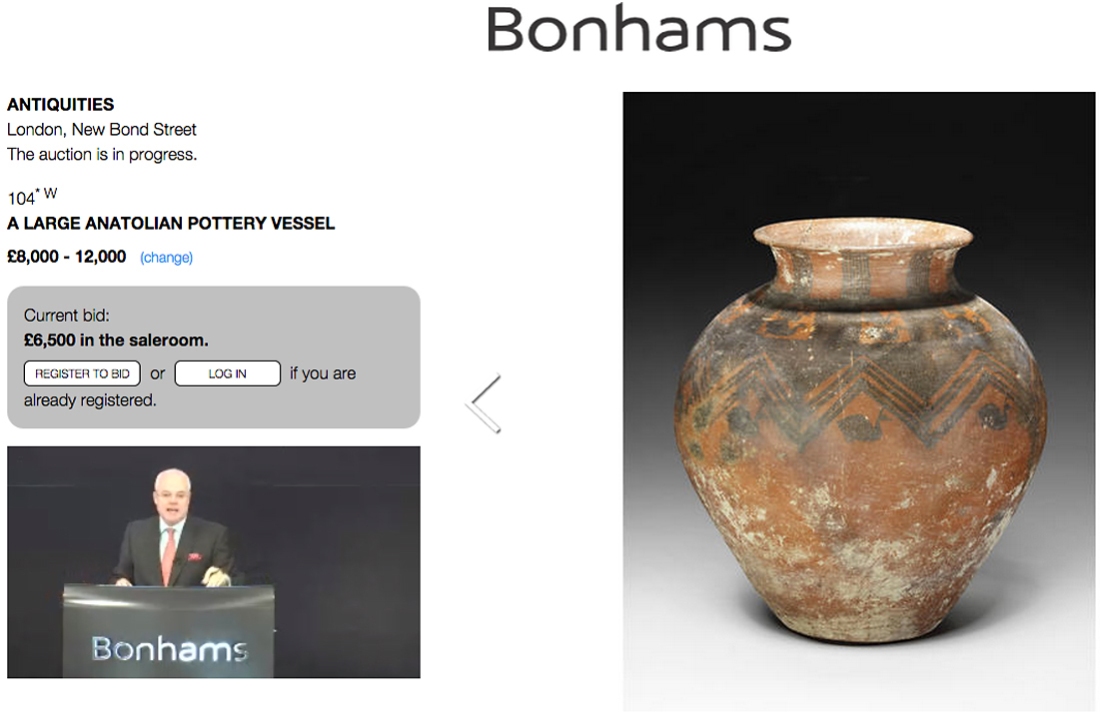

Lot 104: French private collection of Mrs A. acquired circa 1980.

Lot 104: French private collection of Mrs A. acquired circa 1980.

Lot 108: Private collection, Switzerland, acquired in August 2003. European private collection, UK and Switzerland, formed in the 1970s and 1980s. Accompanied by a thermoluminescence test from Oxford Authentication.

Lot 108: Private collection, Switzerland, acquired in August 2003. European private collection, UK and Switzerland, formed in the 1970s and 1980s. Accompanied by a thermoluminescence test from Oxford Authentication.

Lot 117: German private collection, acquired at Dr Hüll auction house, Cologne, 12 April 2012, lot 691. Mr Schahpur Katebi Collection (1926-2013) , received as a gift from the Shah of Persia after discovering the coffin during an excavation campaign in the Amlash region in the 1950s. Mr Katebi brought the coffin with him to Basel, Switzerland, in 1979, and subsequently to Cologne, Germany, in 1981. Accompanied by a copy of a shipping document dated 1981 and by a letter to Mr Katebi dated 28 January 1983, referring to the publication of the coffin. Published J. Curtis, ‘Late Assyrian Bronze Coffins’, in Anatolian Studies, vol. XXXIII, London, 1983, pp.85-89.

Lot 117: German private collection, acquired at Dr Hüll auction house, Cologne, 12 April 2012, lot 691. Mr Schahpur Katebi Collection (1926-2013) , received as a gift from the Shah of Persia after discovering the coffin during an excavation campaign in the Amlash region in the 1950s. Mr Katebi brought the coffin with him to Basel, Switzerland, in 1979, and subsequently to Cologne, Germany, in 1981. Accompanied by a copy of a shipping document dated 1981 and by a letter to Mr Katebi dated 28 January 1983, referring to the publication of the coffin. Published J. Curtis, ‘Late Assyrian Bronze Coffins’, in Anatolian Studies, vol. XXXIII, London, 1983, pp.85-89.

(Note this was amended by the time the item came under the hammer, as I will comment on below. Not sold.)

Lot 123: UK private collection, acquired in the 1970s.

Lot 123: UK private collection, acquired in the 1970s.

Lot 124: Private collection, Switzerland, acquired in August 2003. European private collection, UK and Switzerland, formed in the 1970s and 1980s.

Lot 124: Private collection, Switzerland, acquired in August 2003. European private collection, UK and Switzerland, formed in the 1970s and 1980s.

Lot 128: French private collection of G.D, acquired in about 1975.

Lot 128: French private collection of G.D, acquired in about 1975.

Lot 140: Find spot Pucklington area, East Yorkshire. Treasure report 2013 T184. PAS Database number NLM-1A8B56. Accompanied by a copy of the release letter issued by the British Museum, indicating that the panel was considered under the Treasure Act and disclaimed by the Crown.

Lot 140: Find spot Pucklington area, East Yorkshire. Treasure report 2013 T184. PAS Database number NLM-1A8B56. Accompanied by a copy of the release letter issued by the British Museum, indicating that the panel was considered under the Treasure Act and disclaimed by the Crown.

Lot 146: UK private collection, England, acquired in the 1970s. Accompanied by a copy of an insurance valuation from 2002.

Lot 146: UK private collection, England, acquired in the 1970s. Accompanied by a copy of an insurance valuation from 2002.

Lot 159: Dr Güngör Tezel, Germany, acquired between 1964–1974.

Lot 159: Dr Güngör Tezel, Germany, acquired between 1964–1974.

Lot 160: Property of the Archaeological Institute of America, St. Louis Society Inc. Acquired circa 1914 in return for contributing to funding the excavation. Excavated in 1913-14 by the British School of Archaeology in Egypt from Tomb 124 at Harageh, the Fayum, near Lahun.

Lot 160: Property of the Archaeological Institute of America, St. Louis Society Inc. Acquired circa 1914 in return for contributing to funding the excavation. Excavated in 1913-14 by the British School of Archaeology in Egypt from Tomb 124 at Harageh, the Fayum, near Lahun.

Lot 160 is described as “An important Egyptian tomb group from Harageh Middle Kingdom, 12th Dynasty, probably the reign of Sesostris II , circa 1897-1878 B.C.” Its value, to collectors as much as to all of us, lies particularly in its provenance, which brings together a group of disparate artefacts known to have been buried in a grave.

Hand on heart, I chose these pieces purely because of their intrinsic interest – I hadn’t read the catalogue in advance, and I wasn’t looking at it as the sale progressed. These were just things I thought looked nice.

Where does all this stuff come from, so well preserved yet so vaguely provenanced? And what’s odd about this list?

Here’s a hint.

The Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, an international treaty designed to counter illegal and immoral traffic in art and antiquities, was adopted by UNESCO in 1970.

It’s regularly referred to as a standard in antiquities export matters. For example, the UCL Institute of Archaeology says it supports the convention in its “Policy regarding the illicit trade in antiquities”. The presumption is that any antiquity which left its country of origin after 1970, with no evidence of having legitimately done so, was illicitly exported. Its current possessor cannot be said to have undisputed legal title.

Going through the list above, how many artefacts pass that criterion? How many can show they were either exported before 1970, or were legitimately exported after? You have to be careful how you read the “provenances”. Lot 79 (“private collection… since the 1960s”) might sound OK, but who’s to say what was acquired after the 1960s? Lot 81 (“formed between 1965-1985”) could be pre-1970, but equally may not be.

In fact, only three lots come with apparently unequivocal data implying they do not to break the UNESCO convention.

Lot 140. An Anglo-Saxon piece from Yorkshire, this has not left the country where it was made. It was found by a detectorist in 2013, and recorded by the Portable Antiquities Scheme based at the British Museum (as the photos above show, a small piece of red garnet seems to have been fitted since the record was made, when the bottom panel was described as “set with four small rectangular garnets, three of which survive”).

Lot 117. Mr Schahpur Katebi received this coffin as a gift, we are told, from the Shah of Persia, after discovering it in the 1950s. He brought it with him to Switzerland in 1979. So it would seem, though it may have left its country of origin in 1979, the coffin had been gifted by the Shah long before. Yet no! Bonhams changed the catalogue entry, which, as you can see above, no longer explicitly says Mr Katebi had any right to ownership. Perhaps that’s why, this morning, an item with an estimated sale price of £100–120,000 failed to sell, raising only £85,000. Buyers have standards.

Which leaves:

Lot 160: Property of the Archaeological Institute of America, St. Louis Society. Where it apparently still remains.

Oh, and regarding Lot 108. I have no wish to imply that Oxford Authentication knowingly lent its name to support an illegally exported antiquity. I would be pleased to publish any evidence they would like to show me to put that right. Part of my concern is that salerooms like Bonhams seem to be cavalier with provenance evidence. Surely they have more information about some of these than they have published? Let’s see it, we would all benefit.

Hi,

Just FYI: The Metropolitan Museum of Art (NYC) has bought the Harageh tomb group. Thus, it will be going to an institution where it can be shared with the public and available for study—just as the excavators and the Egyptian government originally intended.

Of course, that is good news. It does not, however, get the AIA St. Louis Society off the hook, or anyone else who might be thinking of doing the same thing with artefacts that have a similar history, for its scheme to sell broke the principle behind the original acquisition, which was that the artefacts should stay in a public collection. It could have offered them directly to the Met, but chose instead to put the group up for sale in the open market. As it did with lot 162 in the same sale (an Egyptian alabaster-travertine headrest from Harageh, also excavated in 1913–14 by the British School of Archaeology in Egypt), which was sold to a private collector for £27,500: https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/21928/lot/162. See http://abcnews.go.com/Entertainment/wireStory/auction-ancient-egyptian-relics-averted-25947017

It’s a complete scandal that such items are not owned in the public interest!

We know that 85-90% of the antiquities from Iraq are now in private investors hands and the knowledge scientists could obtain from further study of these artefacts is now lost – maybe forever?

I have no doubt that the same percentage of OUR antiquities are still in private collections unknown to researchers, leaving a knowledge gap that could solve some of prehistories fundamental questions. This lost ‘treasure’ would give us clues to the past has we have recently seen in the display and detailed modern research of the ‘Bush Barrow” gold grave goods that produced the unfortunate nonsense that these finite pieces were made by ‘Child Goldsmiths’.

The fact that our ancestors were far more skilled and talented (and had better eye-sight) than have been given credit to date is of great scientific interest and historic importance – although the cheap unsupported headlines lends more to the ‘red tops’ that real scientific evidence.

RJL